Lessons for rolling out the One Big Bill: Can states manage Medicaid changes?

As states prepare to manage much work to implement the aspects of the One Big Bill (H.R.1), lessons can be learned from states' inability to manage the work they already are doing

August 5 — The passage of H.R.1, the “One Big Bill” is leading to plans to implement its many provisions affecting Medicaid, including importantly work requirements, more frequent eligibility determinations, verifying enrollment eligibility, and more. Can the states manage these new provisions?

One way to determine the answer to this question is to look at how well the states are currently doing at verifying eligibility, processing applications, and managing important consumer resources like call centers. Evidence from Missouri can show that the state’s resources to manage Medicaid are already stretched and challenged, at a time when they will be asked to do a lot more.

It is these challenges recipients face when trying to enroll, manage or verify their enrollment that led the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and others to conclude that as many as 11 million recipients would lose Medicaid coverage over time, as the provisions of H.R.1 are implemented for work requirements and verification of eligibility.

The findings below are based on analysis by CAHSPER at Washington University in St. Louis of state of Missouri Family Support Division data and data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, posted on their website.

Annual Renewals and Verifications of Enrollment

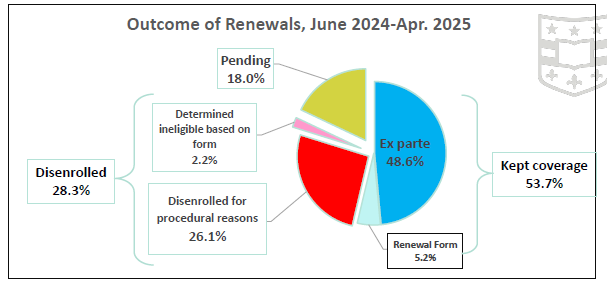

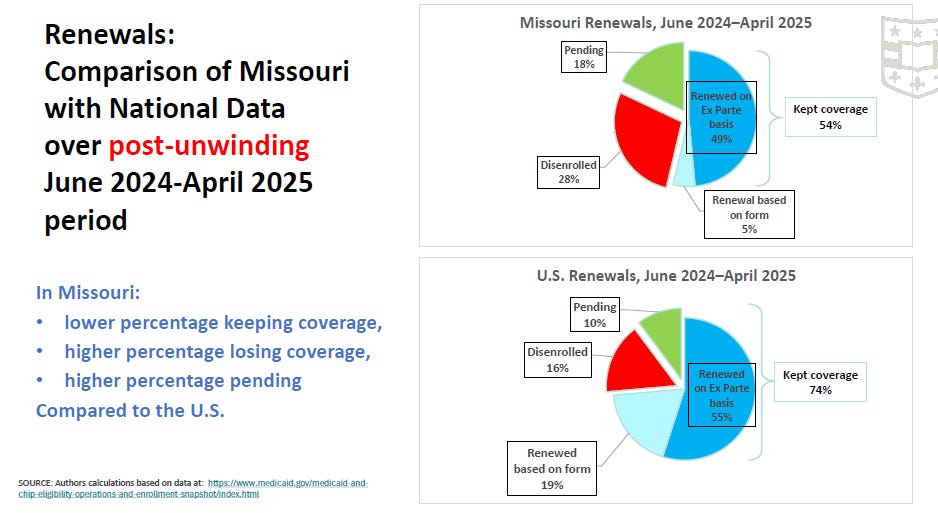

States are currently required to verify that a person on Medicaid is indeed eligible for remaining on the program once per year. Missouri is currently in the process of verifying enrollment for all of the 1.5 million people on the program, and has completed 11 months of that reverification (it takes one year to work through all of the applicants) from June 2024 to April 2025. Using the month-by-month reports from CMS. It is also useful also to compare these results to what happened in Missouri during the period called the “unwinding” when every person on Medicaid who was there during the Public Health Emergency was authorized to be reverified. These conclusions about the outcomes of these annual renewals can be made using eleven months of the current renewal process (see graph as well):

54% of recipients (601,545) have had their Medicaid enrollment renewed;

28% have lost coverage (317,316), been disenrolled, and

18% of the recipients (201,227) had their verification pending.

Several things about these are of note. First, a higher proportion of recipients are losing coverage in Missouri (28%) than are losing coverage across the U.S. (16%). Second, a higher proportion of recipients had their applications for renewal pending in Missouri (18%), as compared to the U.S. (10%).

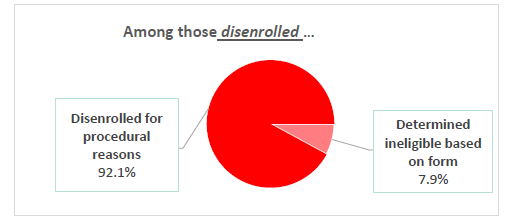

Perhaps most importantly, in Missouri, while some recipients lost coverage because they are no longer eligible (e.g., their income rose, they left the state), a very high proportion of those losing coverage are losing the coverage for “procedural reasons.” Procedural reasons include but are not limited to: the application for renewal was lost in the process; recipients never received the application for renewal, perhaps because it was sent to a snail mail address that is not current; recipients received the request for renewal but got confused about what was needed to be done or were overwhelmend by the process; or the Family Support Division failed to process the paper work that was submitted or the information was not entered into the State’s computer system on a timely basis.

Importantly, in the last nine months reported (June 2024-April 2025), 92% of those who were disenrolled (lost coverage) lost that coverage for procedural reasons and only 8% because they were determined ineligible through a form received (see graph below).

This level of 92% is one of the highest in the nation, and much higher than the level of procedural problems (78%) observed in Missouri during the unwinding. Across the U.S. only 65% of those who lost coverage lost it for procedural reasons. These data suggest there are breakdowns in the verification process in Missouri that are worse than in other states.

Call Center issues

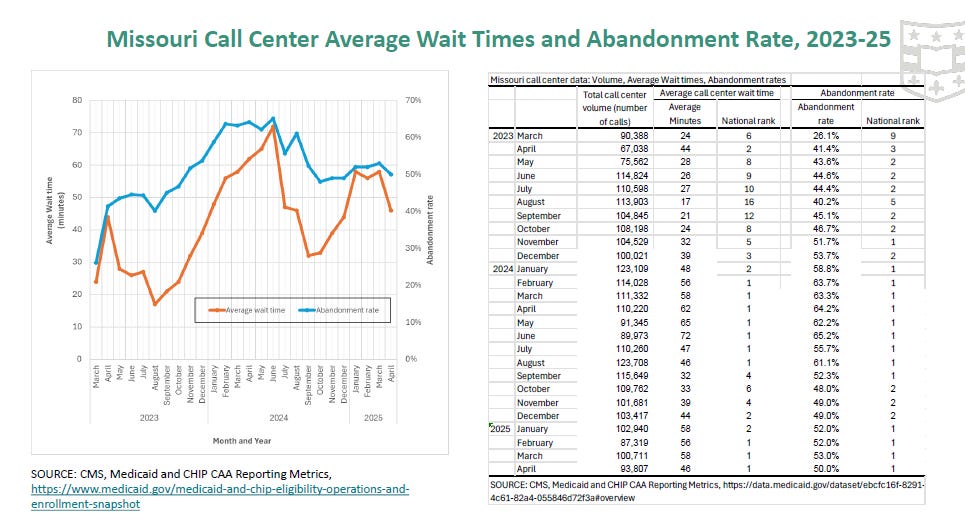

Another indicator of problems in Missouri comes from analysis of the state’s data in running the “Call Centers”. The Call Centers are where recipients make phone calls for assistance with any aspect of the Medicaid program. In Missouri, the call center data suggest that the state has the worst outcomes of any state in the country. In particular the graph shows that the average call to resolve problems took 46 minutes in Missouri, the longest time for a call of any state in the country. Also the data from CMS shows that half of those who initiated a call dropped the call while they were waiting, also the worst outcome in the country.

These data suggest the Call Centers are likely understaffed or lack the training or incentives (pay) to be efficient. The data also give some indication of why recipients may end up having procedural problems with renewing their coverage.

Processing New Applications

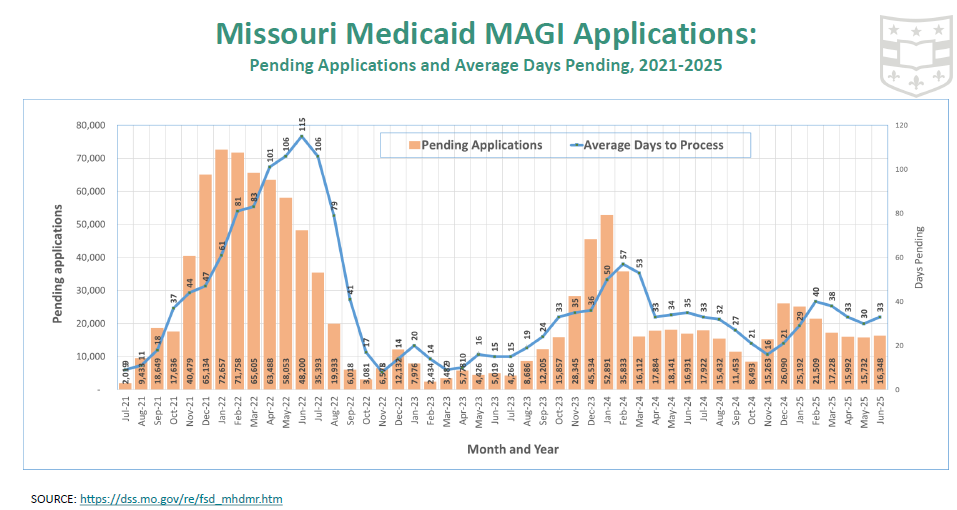

Another indicator of how well the state is doing at serving Medicaid recipients is to explore the level of applications received and how quickly the state processes these applications. All states are required to process a new application for Medicaid in 30 days or less (new MAGI applications). Yet, in recent years, two indicators of stress in the system have been indicated. First, the state has had in recent months a large number of pending applications, leading to long delays in processing the applications (see graph). For example, in February 2024, as the open enrollment period closed, the average number of days to process an application reached 57 days, leading CMS to intervene and demand changes. To Missouri’s credit, that average days pending has dropped to 33 days in June 2025, though the days an application remains pending rises every year during open enrollment.

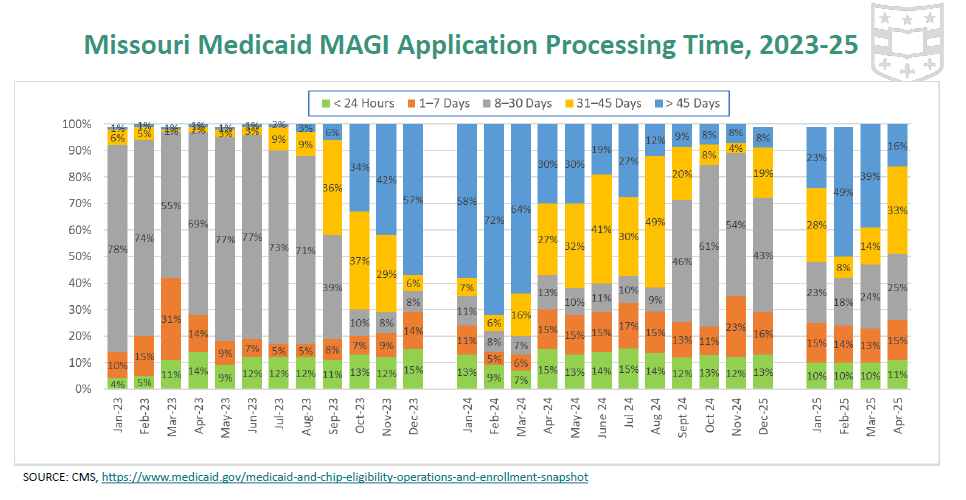

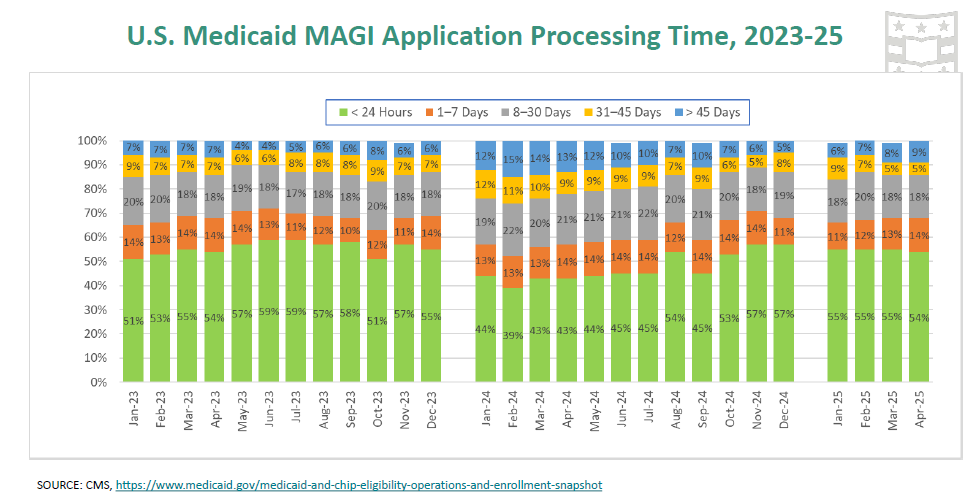

Although there has been improvement in the processing time of new applications, Missouri generally takes longer to process new applications than other states do (see graphs). For example, in April 2025 in Missouri 49% of applications took 31 or more days to process (which is longer than required), while this was true of only 14% of applications across the U.S.

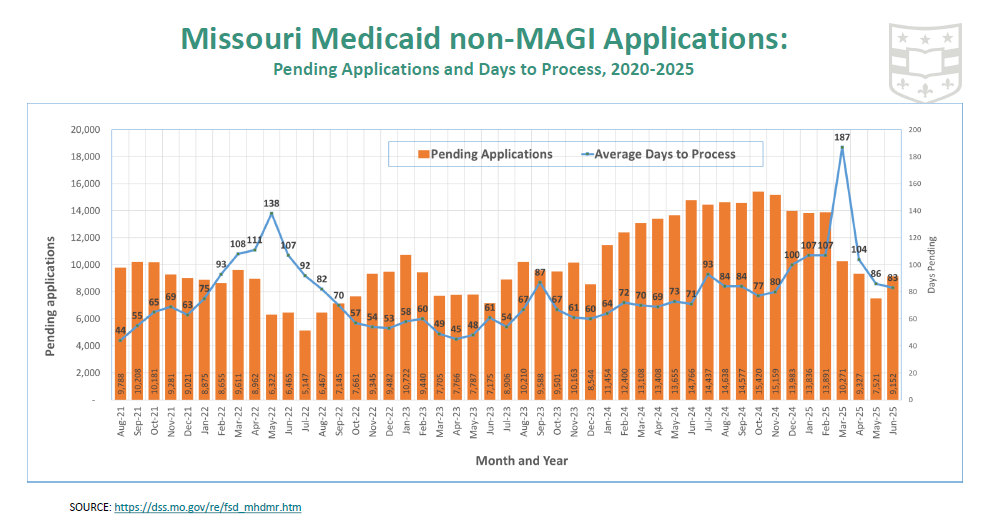

Finally, note that a recipient applying for coverage as an aged, blind or disabled (ABD) recipient (also known as “non-MAGI” eligibility groups) face even longer delays in processing applications in Missouri: in June 2025 the average days to process a non-MAGI application was 83 days, though this was a significant improvement over recent months as the state cleared a lot of applications that had been pending for months (sometimes six months or more). It may take longer to process non-MAGI applications because the applicant has, for example, to have their disability status reviewed.

Conclusions and Implications

As noted here, one state (Missouri) has been experiencing significant challenges in processing the number of new applications to Medicaid, processing annual verifications of the enrollment, and providing basic services such as an efficent call center.

When the states are required to do much more under the provisions of recently-enacted H.R.1 (One Big Bill) need to be implemented, it seems likely that the problems facing recipients will become even worse. For example, the states will now be required to verify annual enrollment for Medicaid expansion enrollees twice per year rather than once. Also the states will now be required to enact a work requirement for adult recipients aged 19-64, with some exceptions, and to make that determination upon initial application to the program as well. This means the states will be required to do 3-4 times as much work for every recipient annually, when in some states such as Missouri the hard working staff are already stretched. The understaffing of MOHealthNET has been raised as an issue, but a proposal to hire more staff was not approved in the 2025 legislative session.

__________

Report prepared by analysts at Center for Advancing Health Services Policy and Economics Research (CAHSPER). and School of Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis.